|

|

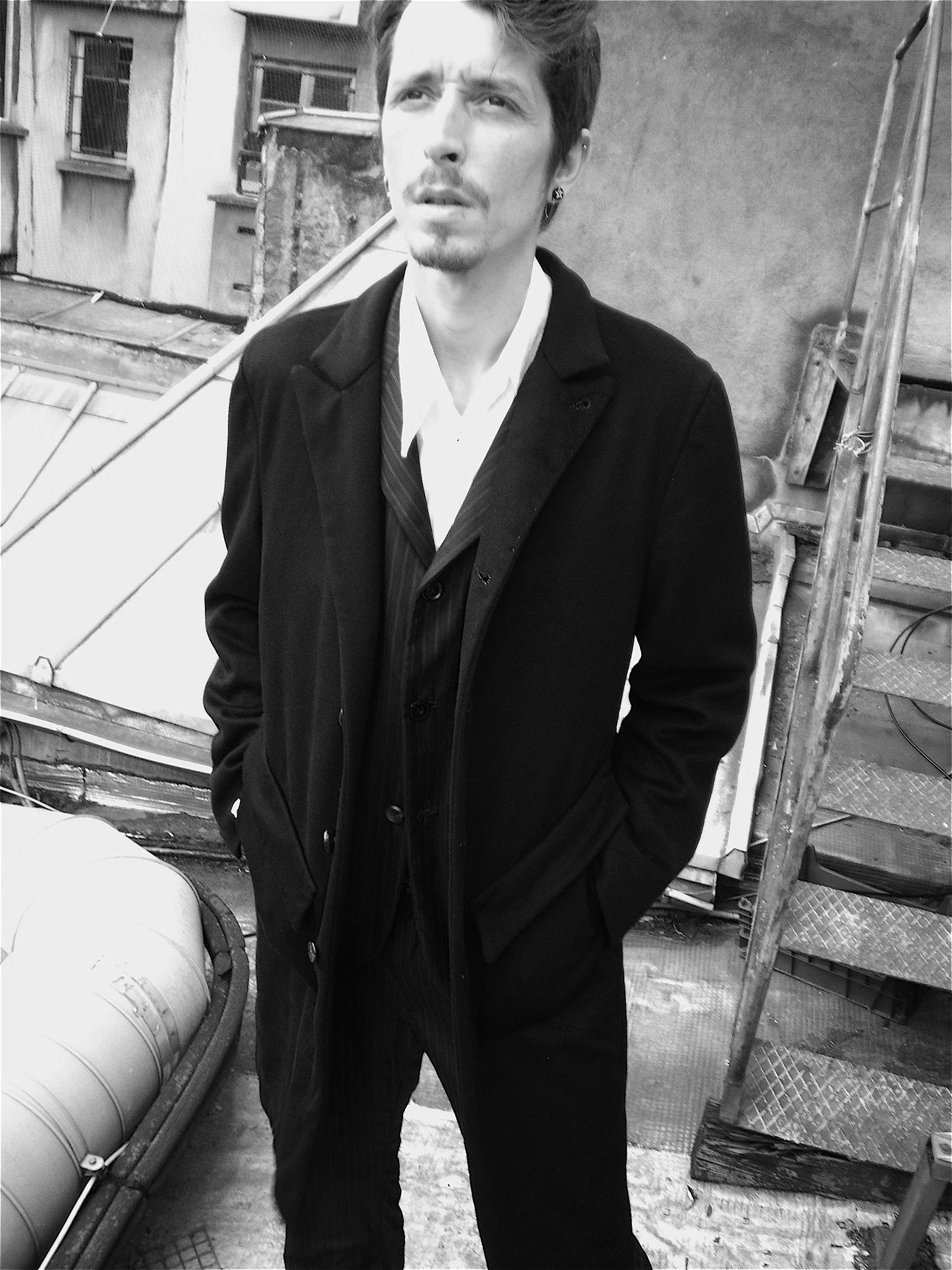

Geoffrey

B. Small

Superlux hand

made waistcoat in hand dyed pure Alashan

cashmere woven by

the oldest

wool mill in the world, Fratelli Piacenza

1733.

Scoute

sat down with Cavarzere Venezia based, American

born creator

of hand-made garments Geoffrey B. Small during

last Paris men’s fashion

week to discuss his personal journey through the

changing fashion

landscape of the last thirty years and his

status as the American

designer with the longest running Parisian

presence.

While

tailoring Renaissance man Small’s past

experiences and vision

for the future are truly enlightening, let us go

back a step and make

explicit where Scoute stands regarding Fashion,

that magnificent and

horrible word that we sometimes fear to utter

aloud, in the vain aim of

avoiding being associated with frivolity and

faddishness.

There

has been talk of a Scoute aesthetic, a taste for

the macabre,

brooding clothes of designers that thread the

dark corners of the world

of, well, dressing up people to look dangerously

cool. Some would say a

thin veneer of ready-to-wear aggression,

available to whoever has the

fortitude of spirit and wallet to buy his entry

into the black-clad

elitist club. This derisive outlook overlooks

the true center of what

we stand for. What those brands, shops and the

passionate individuals

who are at their core share is not so much an

aesthetic stance as an

ethical one.

Consequently,

we believe that presenting Geoffrey B.

Small is not

only an introduction to the work of an important

designer but an

exemplary illustration of that ethical stance.

That his work looks

different from what you would expect to see in

Scoute is merely a sign

that you should revise what are your assumptions

regarding the

magazine’s mission.

The

Geoffrey B. Small narrative

|

|

|

Let us go back to a time

far, far away when the Italian men’s

magazine, L’Uomo Vogue, presented new and exciting

designers, in tune

with the world they lived in and devoid of the

stultification that

would stop them from morphing to continue to

reflect it. This may seem

ludicrous if you never had the chance to see the

magazine in the 70s

but it once presented something beside cocktail

dresses worn by

celedebutantes, star designers and dream weekends

in Spanish villas

reminiscent of the manicured emptiness Antonioni

relentlessly exposed

in his films. Two promising unknowns called Armani

and Versace were

unleashed in a terse, two paragraphs blurb at the

back of a 1977 issue

and they put forward new silhouettes, fabrics and

philosophy that

captivated the young Geoffrey. Here were designers

that would turn

men’s clothing design on its head and set the pace

for what would be

worn throughout the 80s. Since childhood, Small

had continually

expressed himself through illustrations; |

Hand

made jackets hang dry in the Cavarzere sun

as part of Small's special hand dyeing process.

|

|

|

drawing

the “toys he could not

have” (can a kid ever have all the toys he wants?

Get your children a

pen and some sketchpads!), a passion that evolved

during his

adolescence to sketching clothes he wished he

could purchase, many of

them found at the venerable Boston retail

institution, Louis Boston.

“They were one of the very first

retailers in

America to start

introducing what was really going on at the time

in European design,

especially Italy. I started getting serious about

a career in the

field, and wanted to work there and learn from

them, but it didn’t work

out that way…”

|

|

|

Most

of Small's design pieces are dyed by hand, an

arduous and time consuming process that is

centuries-old.

|

Unable to secure

employment at the

exclusive store of his dreams, Geoffrey started

working at The Gap, a

retail company more open to hiring an

inexperienced 17-year old boy. He

enrolled at a local fashion design school,

spending his days working

the sales floor selling and folding jeans and his

evenings beginning to

learn the prosaic but highly useful techniques of

patternmaking,

construction and sketching.

The year of 1979 turned out to be pivotal for

Geoffrey as, through

his schooling, he was able to participate and went

on to beat over

14,000 entrants, winning the ILGWU “America’s Next

Great Designer

Awards” the largest student design competition in

North America. The

following year Small’s talent was again recognized

at the ILGWU, now

boasting 20,000 entries, by a prestigious jury

composed of the likes of

Bill Blass, Elsa

Klensch, Calvin Klein and Geoffrey Beene.

|

|

|

Geoffrey

would go on to win more design competitions, often

boldly disregarding

the dominant American aesthetic of the times and

surprising juries with

his use of the brash silhouettes and understated

colours inspired by

the movement Giorgio Armani had started in Italy.

Now having caught the eye of a few American

recruiters he was tempted

to make his entry into the world of NYC fashion

houses but he quickly

found out that, although the innovative

silhouettes he inked on paper

genuinely impressed his potential employers, the

need of the American

mass market meant he would have to tone them down

so much as to make

them undistinguishable from the comparatively

bland American designs of

the times. Geoffrey remembers with his typical

humour a meeting with

Stanley Kimmel, the president of Jones Apparel

Group in New York (which

now produces a large part of Ralph Lauren’s

collections), to discuss

his taking over the men’s design position, who,

praising his sketches,

proposed a few, minor, modifications: “Nice

shoulders but we’d need to

make them a little narrower! Excellent waist

suppression but our

clients can be quite portly, let’s remove some of

it! Beautiful choice

of wrinkled fabric, but highly inappropriate for

the bankers and

lawyers that need a more conservative suit!”, the

final result ended up

being so watered down that it was identical to

what the company had

been putting on the racks for years.

|

|

|

“My passion was never to

do what

was already being done by others, especially in

the U.S.. I wanted to

take it to another level. At the time, believe or

not, Milan was the

super-cutting edge of world avant-garde. They were

doing what everybody

was eventually going to do after them. And that’s

exactly what I

eventually wanted to do with my own work. I talked

to other designer

colleagues whom I met in various competitions—all

of them prize-winners

and they were all in the same boat. I realized

then and there, that I

would have to control my own production and run my

own business in

order to be able to design the clothes I wanted

to. Nobody else was

going to make it happen, except me.”

By this

time, beginning to be able to sew, he decided

to start a

small laboratory business, making clothes for

friends using an old

Singer sewing machine and the space available in

his parent’s attic.

This focus on the use of the basic

skills of the trade

and a belief in

self-reliance stayed with him to

this day.

|

Handmade late 19th century 14-button

double-breasted babysoft hand

dyed Piacenza cashmere

and silk jacket.

|

|

|

Without being

part of the

punk musical and artistic movement emerging in NYC

at the time, Small,

always sensitive to social undercurrents, soaked

in the do-it-yourself

ethic of those years and applied it to a calling

of his own.

Do it yourself

These

encounters with the business-minded but

conservative American

market only served to reinforce Small’s DIY

ways. He opted to continue

building his small company and trying to teach

himself the tailoring

techniques of past masters. This, arguably

intransigent way of doing

things, may seem counterproductive for a young

designer trying to break

through but Small readily admits that wanting to

be a designer’s

designer is, to him, worth paying a commercial

price. Geoffrey was and

remains the talented indie act that progresses

at his own pace but

remains relevant, thirty years later, having

seen more high-profile

designers come and go, without ever feeling the

need to put down or

attack those choosing a different way.

The

intensive technical and business experiences of

the

80s would

lead him to become, at the dawn of 1990, the man

behind the leading

bespoke tailoring house in Boston. He offered,

in his Newbury street

ateliers, painstakingly constructed suits for

men and women, counting

among his clients such diverse individuals as

the Governor of

Massachusetts and pop act New Kids on the Block.

|

|

|

Geoffrey shows a deep

respect for the intricate

work of bespoke tailoring, “an honourable

profession when done right”,

as he pointedly reminds us. The relationship is

personal and often

extends over a long stretch of time resulting in

numerous outfits

reflecting the meeting of the tailor and client’s

personalities,

lifestyles and interests. To Small dressing

someone is not a science

where a golden ratio must be respected to ensure

optimal results, but

an applied art that gives credence to individual

quirks. Here the

technical meets the relational. “People talk with

their clothes. They

say who they are, or who they want to be. A great

tailor has to get

into people’s heads, know their bodies and their

needs, and then create

and execute the very best solutions for that one

person. You have to

really know your client. And you have to be a real

master of your art

and craft. Unlike runway ready-to-wear, you can’t

fake it. You have to

look your customer in the eye, right there in

person. There is nowhere

to hide.”

With

that being said, Geoffrey after almost a decade

and half of

learning the tradition now felt ready to add to

the fashion symphony a

few notes of his own, and that is why he started

showing ready to wear

collections in Paris in 1992, notably presenting

his second collection

at the original Paris sur Mode salon organized

by Jean-Pierre Fain, an

alternative event held outside traditional

venues, on the banks of the

Seine. Fashion insiders had the chance to

discover his work alongside

the comeback collection by Roberto Cavalli and

the very first Carpe

Diem collection by Maurizio Altieri.

|

Hand washed Piacenza cashmere

& wool

topcoat with real

horn buttons. artisan-made

in Parma.

|

|

|

“It was exciting.

Nobody from America

had ever showed in Paris before us except

Patrick Kelly,

who had moved there and died very young, and

Oscar de

La Renta who of course was

very

classic and

ladies-who-lunch. And

nobody had ever

tried to do Paris avant-garde from

the

U.S.. We were the first, and we had to go up

against the likes

of Comme, Yohji, Martin, Helmut Lang, the

first-wave of Belgians (Ann,

Dirk,), all of them pioneers. And believe me, they

were kicking out

tremendous work in those days; the best in the

world. At the time

nobody in the circuit thought Americans could even

hold a candle in

Paris…could create first-in-the-world design work,

American designers

were known strictly as giant commercial copiers

who sold only in their

home country. We were poor, went over there on a

shoestring. But we

were hungry, and focused on our Art, and made an

impression when we

started, and after a few years there was a wave of

Americans showing in

Paris from Jeremy Scott to Marc Jacobs, to Rick

Owens and even Tom

Ford. Prior to us, there was no one. We opened the

door. People would

ask us why do you show in Paris instead of New

York? I always told them

Paris is the most competitive designer arena in

the world, it’s where

the Art form lives or dies. Each time you get back

in, it makes you get

better.”

To this day Geoffrey B. Small stills

present

collections in Paris,

now eschewing runway presentations to focus on the

visceral experience

of the showroom, an environment where the clothes,

unadorned by

theatrical flourishes, are there to be touched and

viewed as they will

be approached in shops and seen in the wardrobes

of discerning wearers.

Geoffrey remains to this day the American designer

with the longest,

uninterrupted presence on the Parisian fashion

calendar (now on his

63rd Paris avant-garde collection), having been

over the years praised

by Collezioni, Vogue, Women’s Wear Daily and the

perceptive Pierre

Bergé. You may also remember a feature on his 2006

collection,

“An Ode to Toussaint Louverture”, shot by the

ever-present Karl

Lagerfeld.

Tradition and modernity

|

|

|

While the Geoffrey B.

Small story presented

earlier may be construed as a run of the mill rag

to riches narrative,

replete with references to humble beginnings and

concluding on the high

note of Parisian consecration, it mainly serves to

highlight his

approach to learning and growth. Having taken to

heart the mantra of

Mr. Armani, who stressed the importance of knowing

the entire process,

Small took it a step further and elected to take

direct control of it.

Most fashion companies are run like typical

corporations where the

skills that are judged central to the brand, such

as sketching and

design are kept in-house and everything else,

production being a major

example, is subcontracted. In a sense this mirrors

the transition from

art to commercial art enterprise that such high

profile conceptual

artists as Damien Hirst and Takashi Murakami,

inspired by Andy Warhol,

have perfected by coming up with ideas and overall

designs and

commissioning a third party to ensure production.

|

Hand tea dyed Varese

superfine pure linen

hand made jacket and waistcoat.

|

|

|

While

the final product is often of high technical

quality, the value is mainly derived

from the idea and the “branded image” of the

artist. We are reminded of

the exchange between Hirst and one of his

collaborators handling the

actual creation of a series of dot paintings,

where she requested he

sign a work she made for herself, knowing full

well the value resided

in the provenance of the signature and not the

physical object.

Small

has a different approach, like a traditional

artist or

artisan, he puts as much effort in the crafting

of his garments as he

does in perfecting the designs. “Most consumers

and designers don’t

understand that the making is

the design. A designer is always limited by his

production. You’re only

as good as what your production is capable of

making. The better we can

make things, the better the things we can

design. To design the best

clothes in the world, you have to be able to be

the best clothes-maker

in the world. This has been our continuing

mission since 1979.”

This

applies to his supplier network as well. With

almost a decade

in Italy, not in Milan, where virtually nothing

is made anymore, but in

the rural hinterlands across northern Italy

where the real guts of the

Italian textile and clothing industry are found,

he has slowly built up

tight relationships with the very best fabric,

material and accessories

makers in the country—the absolute top of “made

in Italy.” From the

world’s oldest woollen mill and greatest

cashmere house Fratelli

Piacenza in Pollone Biella (founded in 1733), to

the last remaining

handmade button-makers in Italy (Parma), to

individual medieval artisan

specialists in shoe-making and metalworking

design—Small’s ability to

make unique, beautiful and valuable works

continues to expand deep

roots backed by an ever strengthening

foundation.

|

|

|

For

Spring/Summer 2010 he is going even

further, for the first time being able to be

completely involved in the

making of the cloth itself, that he will, as

before, later cut and sew.

He has developed a unique relationship with

Luigi Parisotto and his

family, who collectively have over a century of

fabric weaving and

making experience. The Parisottos are located

north of Vicenza, in the

town of Sarcedo, at the foothills of the alps.

Small describes their

partnership as the collaboration of two master

artists, going above and

beyond a simple fabric supplier-designer

relationship. Able to discuss

thread count, types of cotton, linen or cashmere

compositions and modes

of yarn spinning and weaving, he can clearly

share his vision for the

completed product and has convinced his partner

to create small runs of

slowly spun, peculiar fabrics, with a tactile

feel of beautiful

irregularity reminiscent of pre-Industrial

materials. To further relay

that unique influence, Small foregoes the final

steps of normal factory

finishing and washing fabrics and handles this

crucial part by hand

himself, going as far as to do every piece in

the bathroom of his

apartment studio in Cavarzere. The normalizing

process of washing and

chemically finishing, helping to give fabric its

smooth, even sheen is

thus subverted, or rather brought back to its

original form, and

results in uniquely wrinkled materials, ensuring

distinct results for

each piece coupled with enormous reductions in

carbon emissions and

chemical impacts to local water and environment.

Taking

advantage of his bespoke tailoring years, Geoffrey

designs,

cuts and constructs each garment by hand with the

help of a small team

of 4 highly trained, dedicated and disciplined

designer-tailor

associates. Casual, uncanvassed jackets with

hand-stitched collars,

real hand stitched buttonholes (a job requiring 8

to 10 minutes per buttonhole),

hand finished sleeve cuffs

with

working buttonholes and,

ultimate rarity, hand stitched lapel holes. |

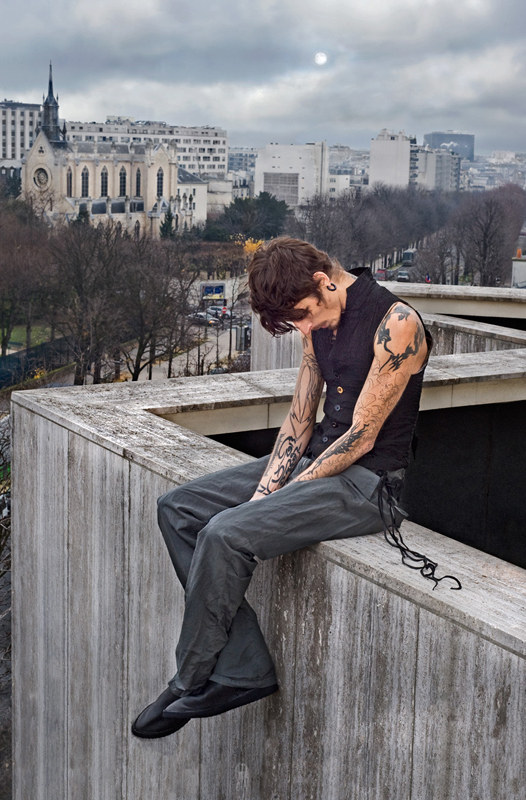

Hand dyed Varese

low gauge handmade pure

linen trouser,

vintage leather suspenders and straw, nut and

wood buttons.

|

|

|

The

pieces, light as

feathers, mould to the wearer’s body and stand as

shining examples of

the disappearing art of hand-made garments. To use

an automotive

example the typical designer suit would be a

Mercedes, the result of a

well-oiled factory process privileging

cutting-edge machinery and a

posteriori quality control with each worker

handling a separate piece

of the puzzle. A Geoffrey B. Small blazer or pair

of pants is a

lovingly crafted custom Rolls Royce, or better yet

a Koenigsegg, each

piece hand finished by a worker who is in fact,

the designer himself,

handling the whole process and ensuring a perfect

integration of all

parts, a time consuming labour of love that few

are willing to even

learn, let alone put into practice. Such an

uncompromising, pre-modern,

and in Small’s view, post-modern approach results

in unparalleled

quality but has its price; less than 500 Geoffrey

B. Small garments are

made each season and they can only be found at

exclusive boutiques

catering to a crowd of passionate clients, looking

for the human magic

of the unusual in a world of mass-produced

repetition. By moving the

fetishism to the process, Geoffrey has managed to

remove it from the

commodity, creating an item that derives its value

from the quality and

the spirit of its construction, materials and

design.

The designer & the world in which he

lives; an ethic of fashion

design

I-D

magazine in their classic “Fashion Now” books

profiling top

fashion designers often ask their interviewees

their feeling on the

possibility fashion has of changing the world we

live in, most choose

to dodge the question to concentrate on their

love of pretty shoes.

Geoffrey does not wait for you to ask; he dives

right in to the topic

and makes it the centerpiece of a well-rounded

conversation. To him,

designers are linked to the world they live in

as fish are to the sea,

while his peers may chose to live in a pristine

aquarium he knows the

world affects him and hopes to do his small part

to exert a positive

influence on it.

|

|

|

Hand dyed Vercelli

silk, wool & viscose waistcoat with

Varese silk & cotton superlight hand dyed

trouser.

|

“Fashion is an Art.

That’s why I do it. And

artists have a responsibility to themselves and

their audience. For

those of us lucky enough to still be in this line

of work–To speak the

truth, not lie about it. And to do whatever we can

to make life better

for people, not just an elite few. And these days…

there is plenty to

do.”

Being

based in Italy he has seen the ravages of

delocalisation that

has left large numbers of textile and clothing

workers unable to find

work after the closing of their factories. The

labour market is not

kind to people that only know how to sew a

pocket once their initial

workplace closes. In this light, his urge to get

to know the full

process and to become an iterative learner takes

a prescient edge.

“For

those of us in Italy who are still practicing

masters of our

work in all the related fields, our biggest

|

|

|

concerns

are about finding

and educating a new generation of masters who can

carry the crafts

forward. Otherwise, the skills and the know-how

will be lost forever. I

teach all the time. But it is very challenging

today, and difficult to

find young people willing to pay the real price

necessary for achieving

mastery in an Art. It’s a lifelong commitment, and

it’s not about easy

stardom or quick money. It’s a disciplined way of

life that requires

sacrifice, commitment, talent, passion and

patience. And it’s not at

all easy, especially in the current decade.”

The fashion world has become a way for him to

communicate his

concern to others and act as a mirror in which we

may contemplate the

present. As an American concerned with the

direction his country of

origin was taking after the tragic events of

September 11, he was the

first in Paris to come out publicly against the

upcoming invasion of

Iraq (January 2003), in January of the next year

he presented the

“Brumaire revisited” collection, a

Napoleonic-themed show that preceded

a slew of similarly inspired collections or pieces

by the likes of John

Galliano, Chanel, Dolce & Gabbana, Dior Homme

and Undercover. While

the influence of this landmark 2004 collection on

the fashion scene is

undeniable, it also allowed Small to get across

his position regarding

pre-emptive wars and aggressive international

policies, a subtext that

was not as easy to recuperate as the beautiful

18th century military

outfits displayed on the runway. Finding much

inspiration in the

garment designs of the past and faithful to his

method of assimilation

followed by innovation, he managed to apply the

same mindset to his

messages. The middle-ages were recontextualized in

the years following

2006, as Geoffrey compared growing social

inequalities to a form of new

global feudalism, explored the place of women in

current social

hierarchy, discussed the growing problem of

illiteracy in modern

societies, and introduced some of the world’s

first clothing designed

to address global warming.

|

|

|

Spring/Summer 2010 saw Small put the idea of a

leading-edge sustainable wardrobe, sturdy,

comfortable, multi-purpose

and unique enough to resist years of faddish

changes to the foreground.

In these times of economic and political

uncertainty, a client may

never know when he can purchase clothes again

and these new garments

will remain wardrobe staples long after the

world has underwent

post-apocalyptic changes rivalling the Mad Max

universe, or so we hope.

Suffice to say that once you have tried them on,

the thought of wearing

them day after day does not sound like torture

but clothing nirvana.

|

The

new direction: a visual story inside that

may be more poignant than the

exterior.

Above: special exclusive vintage lining

(Como), handmade

working buttonhole sleeve cuffs.

|

|

|

Special real horn buttons are finished by Small

with 2 different types of West German sandpaper.

"We spend more for our buttons, than most

designers spend for their main fabrics--it's part

of our Art."

|

“To me today’s

avant-garde is about the inside of clothes, how

they

feel and how they last, how they protect you.

People cannot afford to

only deal with exteriors now. It’s not about the

outside anymore. Of

course, it has to look good, it has to fit, and it

has to be cool—but

there are landfills of that kind of stuff

available right now. And the

customer knows it. Show me something that will

keep you alive and

comfortable if you lose your house tomorrow, a

tragedy faced by 1 in

every 50 people in the world in 2008. I feel a lot

of cool designers

and stores are still back in the late 90’s/early

2000’s mentality, but

I lost interest. Been there. Many of them are my

friends. But I am

really on to a different thing. Every piece I make

now has to be

comfortable, really comfortable–good

enough to sleep in. For ten years. It has

to have a visual

story

inside that may be more poignant than the

exterior...

|

|

|

I spend more

on linings and buttons than a lot others

are spending on their main

fabrics. The idea is to have no carbon or methane

footprint, no

plastic, poly, chemicals, landfill problems,

unsustainability, animal

cruelty, human exploitation or

slavery in its

manufacture. We have a

higher component of handwork in our clothes than

any collection showing

in Paris. Handwork is carbon neutral and builds

craft and gives dignity

to people who do the work….Something that’s worth

every penny you

spent, doesn’t hurt anybody, lasts you a lifetime,

makes you feel good,

and yes, looks really good too, every time you put

it on. That’s the

new direction fashion needs to take, and that’s

where I am focused. The

world’s greenest designer concept at the Paris

collections-level.”

|

|

|

While not every designer

discussed by Scoute makes his principles as

explicit and readily intelligible as Geoffrey B.

Small, it is this

shared ethos that draws us to their work. They

have respect for

tradition that follows the dictum of learning,

imitation then followed

by innovation; they treat seasonality as a way to

build upon a corpus

of work instead of an ever-changing attempt at

aimless renewal ; they

value craftsmanship and technical knowledge and

they realize that a

broad cultural horizon that goes beyond fashion is

the way to bring

soul to a design thus capturing that indefinable

quality that makes a

garment a passageway to the wearer’s individual

expression. Human

rapport is central and not mediated by countless

faceless entities;

creators participate in the whole process, from

fabric weaving to

dealing with store buyers.

|

Expensive pure silk Bozzolo Reale

Milan threads used for handstitched buttonholes

and hand detail work.

|

|

|

"It’s

about 30 years of work, people, and resources,

putting it all

together, and making the very best clothes we

possibly can with

everything we’ve got. Then raising the bar one

more time even higher

for the next time… that’s what makes it fun.” |